by John Byrne Barry | Sep 11, 2023 | Design, Wasted

On September 21, I’ll be part of a local author panel at the Mill Valley Library discussing researching and writing about California. I’ll be discussing my 2015 novel Wasted, a “green-noir” mystery set in the garbage and recycling world of Berkeley, as well as my work-in-progress, a historical mystery/comedy based on true events in Sausalito during the houseboat wars in the 1970s. (I’m adapting this novel from “Sausalypso Houseboat Wars Murder Mystery,” the play I wrote and directed this past spring in Tam Valley.)

The event is free. Hope to see you there. Register here.

Other panelists include Daniel Bacon, author of Walking San Francisco on the Barbary Coast Trail and the historical novel Frisco; Susanna Solomon, author of Point Reyes Sheriff’s Calls, More Point Reyes Sheriff’s Calls, Paris Beckons, and Montana Rhapsody; and moderator Joanne Orion Miller, travel writer, short story writer, and author of Shaketown, a novel.

The panel is a partnership with California Writers Club Marin and the Mill Valley Library.

Because I’ll be talking about Wasted, I am percolating, again, on whether or not to redesign its cover, which you can see below.

Wasted is the first novel I wrote — it took more than ten years — and I sometimes think of it as a “lesser” work than my other two novels. (It sold fewer copies and garnered fewer reviews than my other two novels, though I read it again recently and was thrilled with how entertaining it is and how well it captures the zeitgeist of Berkeley, from its recycling movement to its contradictions to its high self-regard.)

Wasted is the first novel I wrote — it took more than ten years — and I sometimes think of it as a “lesser” work than my other two novels. (It sold fewer copies and garnered fewer reviews than my other two novels, though I read it again recently and was thrilled with how entertaining it is and how well it captures the zeitgeist of Berkeley, from its recycling movement to its contradictions to its high self-regard.)

But the cover is a problem.

Set in the gritty and malodorous world of garbage and recycling, Wasted explores rich and resonant themes of reinvention, transition, and discarding that which no longer serves us.

Berkeley reporter Brian Hunter investigates the “recycling wars,” finds the body of his friend Doug crushed in an aluminum bale, and hunts down the murderer, all the while trying to win the heart of Barb, Doug’s former lover, now a suspect in his murder.

Part mystery, part love triangle, and part political satire, Wasted asks the age-old question: How do I act with truth and integrity, make the world a better place, and still get laid?

I designed the cover — I’ve been a graphic designer for decades — and I was happy with it. At first. I thought it was crisp and clean and memorable.

So much so I entered it in Joel Friedlander’s monthly ebook cover design contest on thebookdesigner.com.

Here’s his critique:

This is a very common situation in which a skilled graphic designer brings those skills into book cover design, which is much more tied to conventions.

Obviously the designer is skillful, but the big fail is that the book looks like nonfiction or a corporate publication, and has no trace of what must be the excitement and drama in the story.

Ouch!

As I’ve learned in the years since, the main job of the cover is to tell potential readers what kind of book it is. I’ve failed on that front — Wasted is not a corporate publication or a recycling textbook.

Over the years, I’ve tried other designs, but have not been happy with any of them.

First, I added blood. Better? At first I thought so, but I was not convinced enough to upload the new cover to KDP.

Then I tried the industrial warehouse look. Too busy and ugly. Not an improvement. Though arguably better at telegraphing what kind of book it is.

More recently, because I’m ordering copies to sell at the upcoming panel discussion, I went back to the original, with the recycling arrows, but also with a hint of suspense. Specifically, a woman with a flashlight. I also integrated a corrugated metal warehouse into the background.

I’m leaning toward the one on the right, with the woman with the flashlight in the center. Or rather I was. More on that in a minute.

One last thing, which I was inspired to do by Bay Area Independent Publishers Association (BAIPA) cover design presentation last December by David Kudler, is to design all my book covers in a complimentary way, even though they aren’t a series. You can see below how Bones in the Wash, Wasted, and my novel-in-progress are unified by the layout and typeface, even though the imagery and words are different.

.

.

This past Saturday morning, at the monthly BAIPA meeting, I shared the covers above as part of “Five-Minute Feedback,” and was shocked by the consensus of the group. During our brief discussion, turned out that many people liked the cover I referred to as “ugly,” with the broken windows and bloody hands. But I hadn’t even included it in my final four for the poll. We added as it choice E, and it “won” 70 percent of the vote.

Wow. What an eye-opener. I was so sure the last cover, the woman with the flashlight inside the recycling arrows, would get the most votes. (It got 17 percent.) But that’s because I couldn’t let go of the recycling arrows. Based on the discussion and the poll, one reason the “ugly” choice may have won is because it did not have the recycling arrows, except in a much less prominent way.

I’ve since received several follow-up emails with additional feedback, including one who suggested that I not listen to the 70 percent.

I’m going to sit with all this for a few more days, and I welcome additional feedback in the comments or via email — johnbyrnebarry@gmail.com.

I love designing book covers. But geez, it is hard!

P.S. I also got an email yesterday from someone I designed a book cover for earlier, reiterating how much he and others like the design. So it’s not like I strike out all the time. 🙂

by John Byrne Barry | Jan 21, 2015 | Design

OR

From My Kitchen Cabinets to the Russian Far East

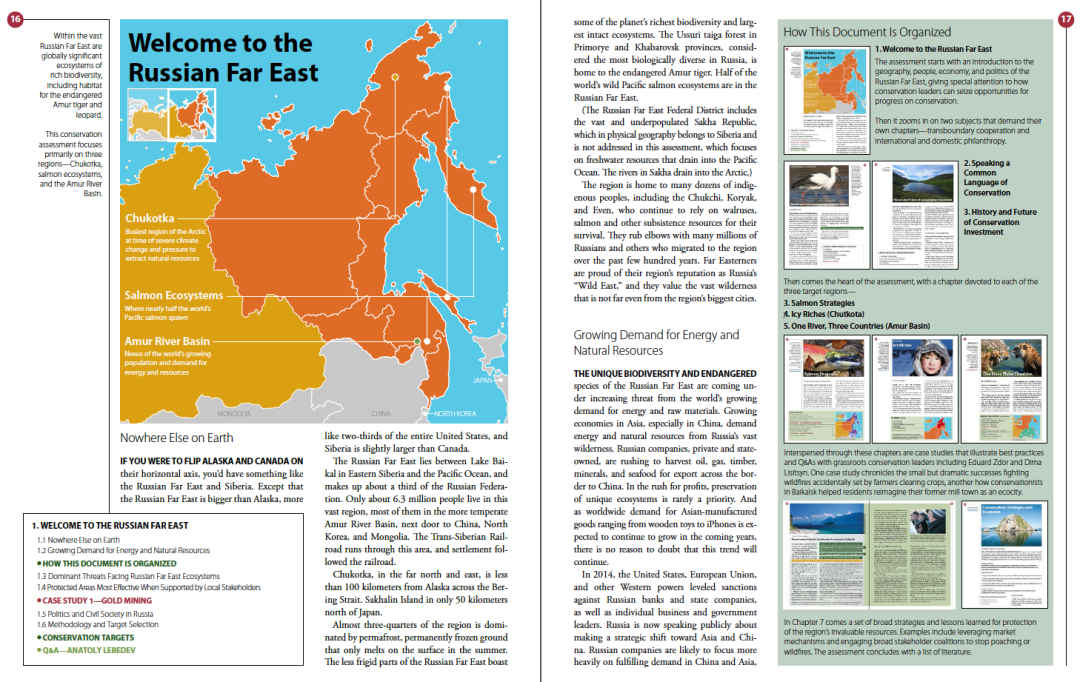

Last year, I devoted many months writing and designing the Conservation Investment Strategy for the Russian Far East—which was about, among other things, growing markets for wild salmon in Kamchatka, scientists and indigenous hunters teaming up to monitor walruses in Chukotka for climate change impacts, mobile fire brigades fighting wildfires accidentally set by farmers burning their fields. More fascinating than you might think.

The client, Pacific Environment, was thrilled with the report and I was proud of it too. It’s some of the best work I’ve ever done.

What I found interesting, though not surprising, was that almost all the kudos were about the design, even though that accounted for only a quarter of the work.

That’s probably because most people didn’t read the entire 80 pages. And those few who did appreciated that the design elements reinforced the message of the document.

It’s a reminder to me, as a writer and designer who identifies more as a writer, that in many cases, design is as important or more important than the words.

My plan here is to deconstruct my design process to see if I can learn from what I did, and maybe others can as well. It’s not that I didn’t consciously make decisions along the way as much as that I’ve been a designer for decades and some of those decisions were almost intuitive. Looking back I can see more clearly what I did.

A word about the writing part. There was heavy slogging along the way—I had to distill hundreds of pages of dry scientific language into a compelling narrative, and there were moments when I was pulling out my hair. It’s not that the content I had to work with boring, though some of it was. But it wasn’t exactly high in entertainment value, so one of my goals was for the casual reader to get the basic message from the decks and captions and headlines.

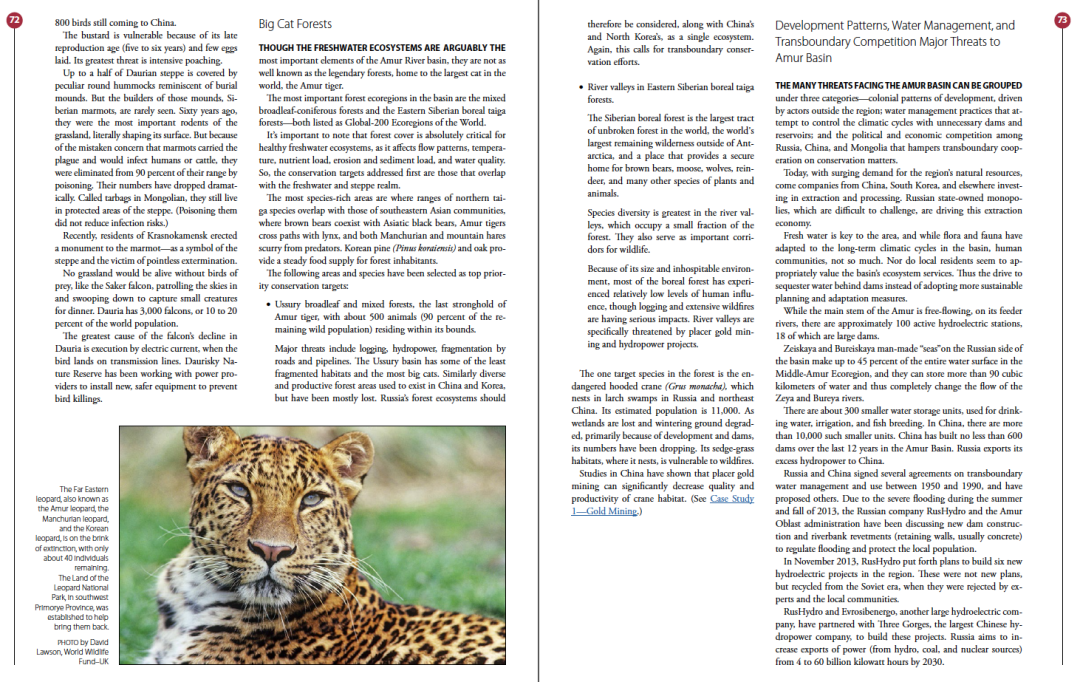

Here’s an example—I didn’t have a photo for this story, but the concept was pretty straightforward, that satellite photos could document pollution much more effectively than a government agent who has to make an appointment to visit the mine.

What Do Readers Read?

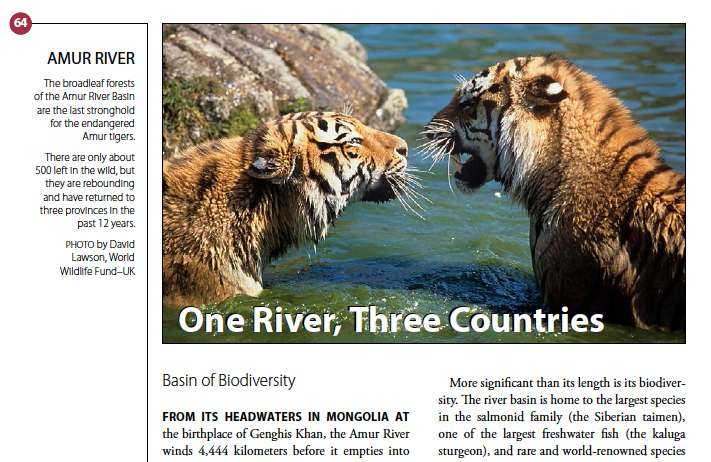

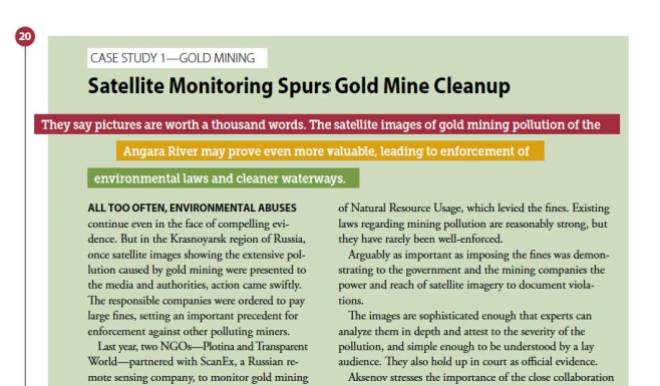

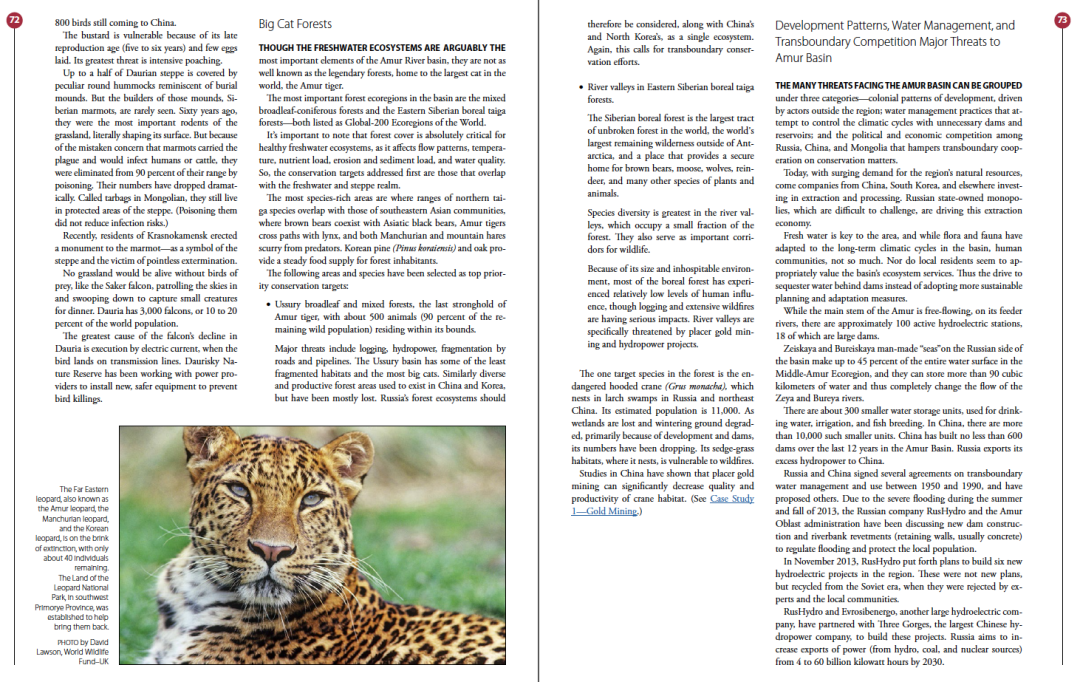

Photos, of course, play a huge role, not just the images themselves, but the captions, which get read, depending on who you listen to, four times more often than the body text. The best captions reinforcing the message of the document. So, for example, the caption for the photo below of two tigers growling at one another doesn’t reference the photo directly, as much as it provides important context—how there are only 500 Amur tigers left in the wild, but they are on the rebound.

There’s no need for the caption to repeat what the reader can see in the photo.

I also looked for ways to feature people, in the narrative and the images. So much of the content I had to work with was scientific, like the names of threatened species, or fishing harvest data.

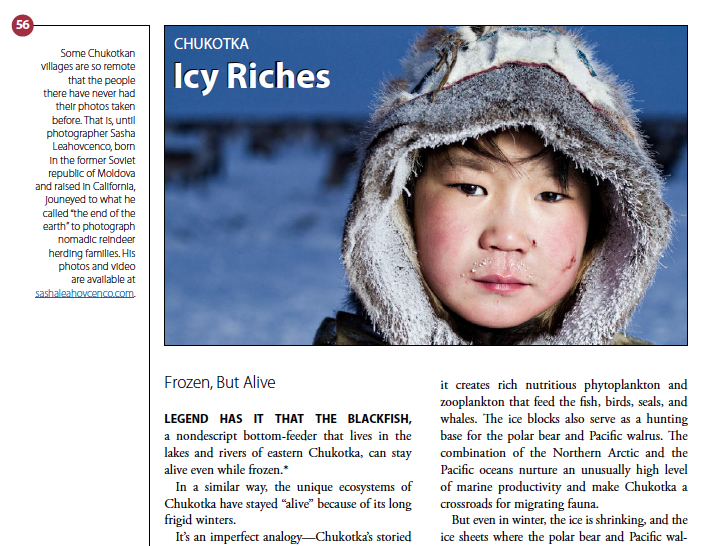

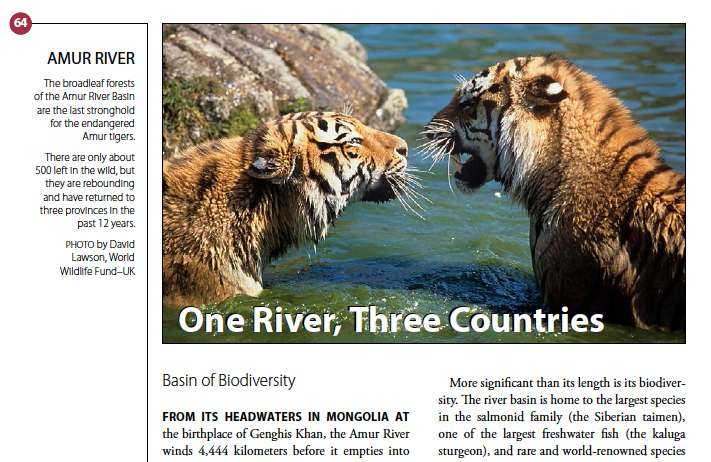

The chapter on Chukotka, which is across the Bering Strait from Alaska, and equally frigid, didn’t have a lot of compelling stories. All of the photos I had to start with were of stark landscapes. None of people. In my search for better images, I came across a wonderful website and story by a photographer from California, Sasha Leahovcenco, who was born in the former Soviet republic of Moldava and journeyed to Chukotka to take photos of indigenous people there, most of whom had never seen photographs of themselves before. He was happy to let me use his photos. Here’s one of my favorites.

Five-Column Grid—It’s Great to Be Odd

Even though I’ve designed dozens of reports like this, I deliberated carefully on what kind of grid to use. Mostly, for reports that are standard 8.5” x 11” size page, I use a simple two column grid, but for something long and complex like this, with maps and photos and charts, I chose five columns, which allows for both uniformity and variation. The default layout was two blocks of text, one two columns wide, the other three. It’s more interesting than two columns the same width.

It also allows for one column of white space when necessary. I found this very helpful for fitting copy. When text was added or cut, and I didn’t want to add extra pages, I could expand or contract the column width and still have a unified look.

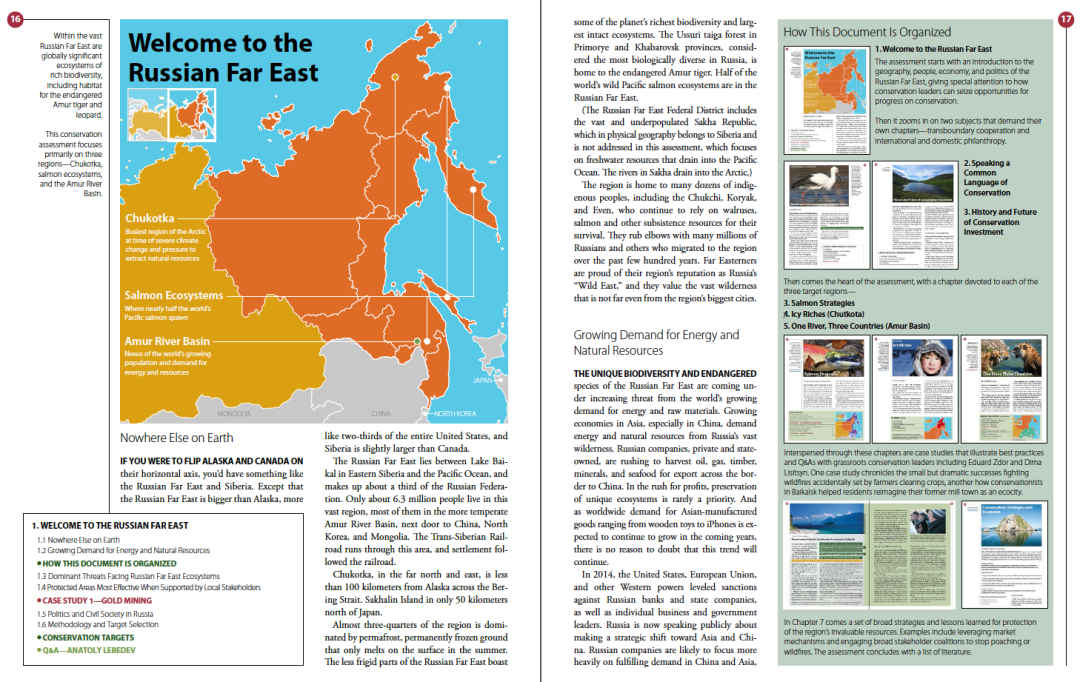

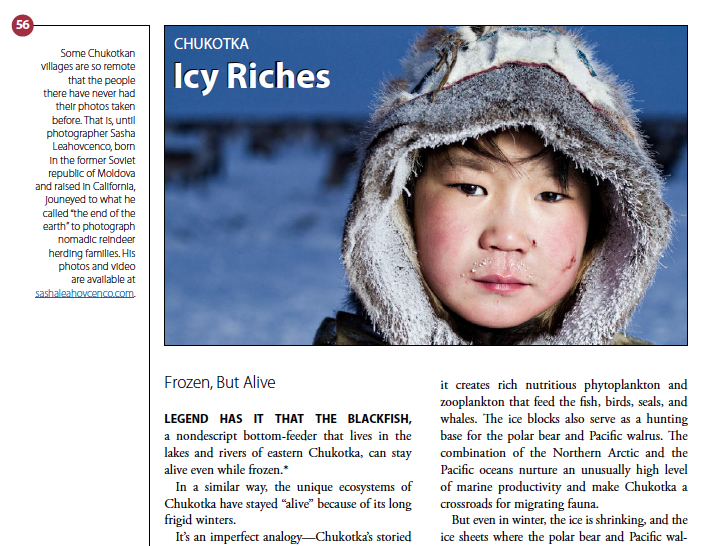

Here are two chapter-opening spreads where the left-most column is primarily white space, and the right page uses the 2 + 3 grid. Then comes a text-heavy page with 2 + 3 on both the left and right side.

Note also how the map, which is a dominant element in the first spread above, is used on a smaller scale at the bottom of the second spread, as a locator map for the particular region being addressed, in this case, Chukotka. Maps are especially important when readers may not know the area, but even when they do, they help anchor the story.

Note also how the map, which is a dominant element in the first spread above, is used on a smaller scale at the bottom of the second spread, as a locator map for the particular region being addressed, in this case, Chukotka. Maps are especially important when readers may not know the area, but even when they do, they help anchor the story.

Another design element that helped orient readers (pun intended) was including a mini-contents box at the bottom of each chapter’s opening page to supplement the map. This was a big and complicated document, and though these mini-tables of contents were redundant to what was in the main table of contents, I wanted to make it as easy as possible for readers to know where they were and what was coming.

Color Bars

Arguably, the most important design decision was to use wide horizontal bars in gold, olive, and rust to feature what I call “decks.” (They are often referred to as “pull-quotes,” but for this project, I more often distilled an important point into a sentence that might been a paragraph in the text.)

Like the grid, the regular use of the color bars contributed to a unified design, but they were even more versatile than the grid.

Because I used the color bars in a slightly different way each time, I was able to use them more than a dozen times without being repetitive. What was consistent was the color palette, the height of the boxes, and the typeface, and what varied was the length and placement of the stripes, and the specific colors. In some cases where there were three lines, I used all three colors. In some cases, all three stripes were aligned on the left. But other times, I staggered them or only used two colors. (In a few places, where I was already using the olive green as a background, I added a fourth color, a darker green to the color bar palette.

Below are a some examples. You can see that the placement, alignment, colors, and length vary, and of course, the words do too, but the palette and typeface keep things unified.

From My Kitchen Cabinets to the Russian Far East

Choosing a color palette is one of the most important parts of a design, and there are almost an infinite number of options.

I knew I wanted warm colors to counteract the arctic content. I started with rust, one of my favorites, and before I realized it, I was working with roughly the same colors I painted my kitchen cabinets in Berkeley a decade ago. (I know I can’t keep using the same colors over and over, but recycling a palette every ten years doesn’t seems to be a problem.)

Back around the turn of the century, my kitchen cabinets were medium brown wooden doors and drawers that were becoming increasingly ugly with wear and tear. On a trip to Mexico, I purchased colorful ceramic (Talavera) knobs from street vendors in San Miguel de Allende, and my plan was to paint the cabinets white and add the knobs for color. The first few I painted didn’t look as interesting as I’d hoped.

So I played with some richer, more intense colors, and after some trial and error ended up with three colors—rust, gold, and olive green. You can see the cabinets here.

Reinforcing the Message, Telegraphing the Character

Design that is visually appealing and memorable is a strong start. But not enough. The most critical element of good design is that it telegraph and/or reinforce the message and character of the content. Is it authoritative? Whimsical? Serious as death? Important, but not self-important. In the case of the Russian Far East document, it was important to get across the comprehensiveness of the report. Because the length of the report and the long list of contributors at the beginning already characterized it as comprehensive, I didn’t need to do much more with the design to reinforce that. Instead, my primary design goal was to make the report more engaging and welcoming. The colors and the maps and the intimate closeups of people helped with that.

Wasted is the first novel I wrote — it took more than ten years — and I sometimes think of it as a “lesser” work than my other two novels. (It sold fewer copies and garnered fewer reviews than my other two novels, though I read it again recently and was thrilled with how entertaining it is and how well it captures the zeitgeist of Berkeley, from its recycling movement to its contradictions to its high self-regard.)

Wasted is the first novel I wrote — it took more than ten years — and I sometimes think of it as a “lesser” work than my other two novels. (It sold fewer copies and garnered fewer reviews than my other two novels, though I read it again recently and was thrilled with how entertaining it is and how well it captures the zeitgeist of Berkeley, from its recycling movement to its contradictions to its high self-regard.)

.

.

Recent Comments